The true sin of Narcissus: refusing the role imposed upon him

“Narcissist.” “Selfish.” “Opportunist.” Three words often used as insults — moral judgments disguised as psychology. But what do they really mean? And more importantly: who says them, and why?

Today, we accuse someone of narcissism when they seem too focused on themselves — when they cultivate their inner world, take care of themselves without asking permission. But in many cases, the accuser is not motivated by ethics, but by a frustrated need: “You’re not giving me what I want from you — therefore you’re selfish.”

“You’re not putting me at the center — therefore you’re narcissistic.”

“You seized the right opportunity — therefore you’re an opportunist.”

It’s a subtle but pervasive mechanism: using moral language as a form of control. A kind of emotional blackmail — often unconscious — that distracts us from a fundamental truth: taking care of oneself is not a crime. It is the first authentic act of love.

Narcissus was not vain

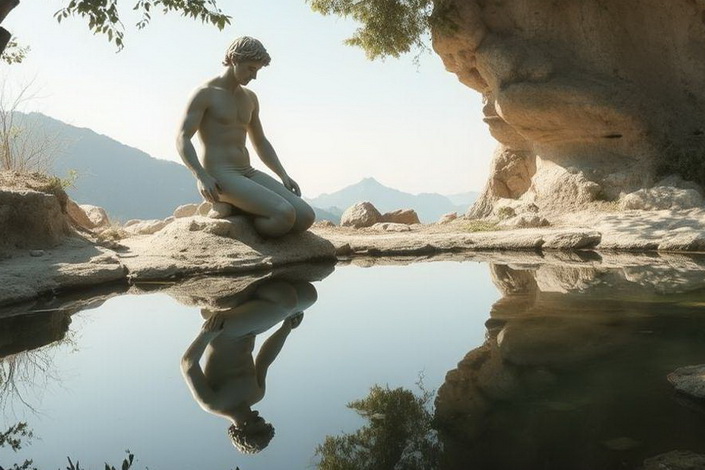

In the version of the myth passed down by Ovid, Narcissus is an extraordinarily beautiful youth, pursued by anyone who lays eyes on him. But he does not return their affection. Not out of cruelty — simply because he does not desire what others expect from him. Not even Echo, the nymph who can only repeat the last words she hears, manages to earn a “yes.” Eventually, a rejected admirer calls upon the gods for revenge. And Nemesis punishes Narcissus by making him fall in love with his own reflection in a pool of water.

It is not a healthy love: it’s an obsession that consumes him, because the image cannot be touched and does not return his affection. Narcissus fades and dies. But the real question remains: What exactly was his sin?

Looking closely, he harmed no one. He made no false promises. He simply said “no.”

The myth, then, can be read differently: not as a condemnation of self-love, but as a symbolic punishment for refusing to play the role expected of him by others — for not making himself available in the “right” way, thus disturbing the social order.

The hypocrisy of “conditional” self-love

This paradox is alive and well today. The same cultural messages that tell us to “love yourself,” “take care of yourself,” “shine in your own light” are quick to turn accusatory the moment we actually do — with clarity, with boundaries, without apology.

Yes, many New Age teachings say, “Love yourself.” But as soon as you do it consistently — with limits, priorities, the strength to say “this is not good for me” — you are labeled narcissistic.

So the question arises: Are we only allowed to love ourselves as long as we don’t disappoint anyone else’s expectations? As long as our self-respect doesn’t threaten others’ need to feel indispensable, loved, or central?

Even Jesus — often cited as the model of selflessness — didn’t say “Love others more than yourself.”

He said: “Love your neighbor as yourself.”

Love for others is measured by love for oneself. It doesn’t contradict it — it presupposes it.

The double standard of language

Within this framework, another contradiction emerges, clearly visible in our everyday language. A few examples:

- We’re told to “seize opportunities” — but if we do it too well, we’re called opportunists.

- We’re encouraged to pursue profit, to make our talents flourish — but if we succeed, we’re labeled exploiters.

- We’re urged to love ourselves, but if we set boundaries, we’re called narcissists.

Language becomes a semantic minefield, where positive concepts turn into accusations the moment we put them into action with conviction.

But it’s not the meaning of the words that changes — it’s the gaze of the one using them. The judgment often comes from personal disappointment, not moral insight. And the person accusing you usually doesn’t want fairness — they want you to be useful again.

A myth about the kind of freedom that unsettles

In this light, perhaps Narcissus isn’t a warning against self-centeredness.

Perhaps he’s a symbol of inner freedom — the kind that scares people. A freedom that is not defined by the needs of others. A freedom that refuses the transaction of pleasure offered in exchange for approval.

So maybe the true sin of Narcissus — then as now — was not loving himself too much.

It was refusing the role that had been imposed on him.

It was saying no — with innocence and firmness — to those who wanted to claim his beauty, his presence, his consent.

And perhaps, for those who are used to living only through others, that is indeed the most intolerable sin of all.

by Bruno